Women are no longer willing to prop up the global economy raising children for free. The result is a global population CRASH

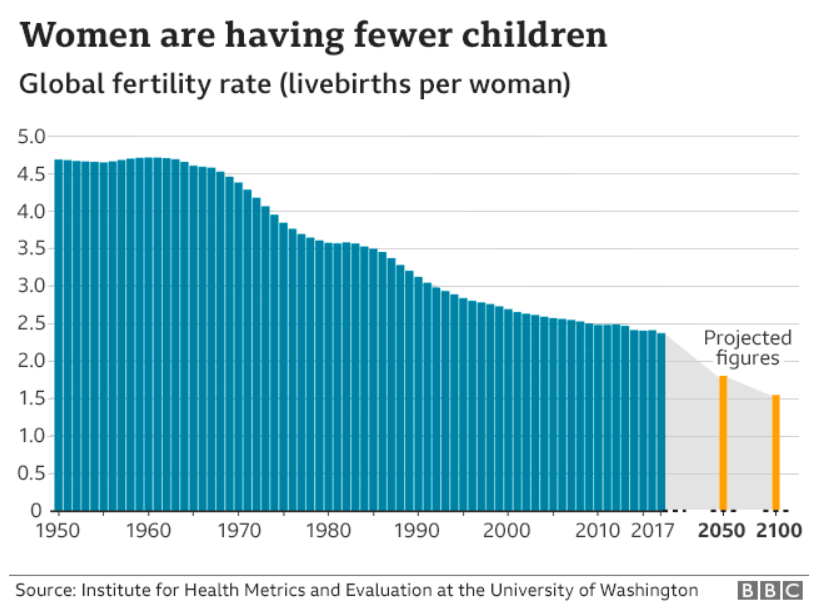

A global crash in children being born which is set to have a “jaw-dropping” impact on societies, say researchers.

A global crash in children being born which is set to have a “jaw-dropping” impact on societies, say researchers.

Falling fertility rates mean nearly every country could have shrinking populations by the end of the century.

Put another way, that means there will be more funerals than births.

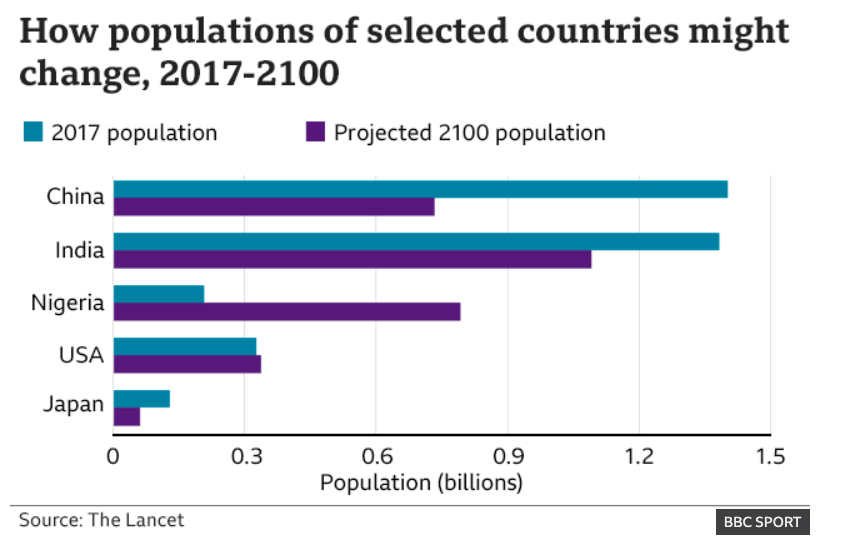

Twenty three nations – including Spain and Japan – are expected to see their populations halve by 2100. Even populous countries such as India and China are facing declines in fertility. 183 out of 195 countries are facing a fertility rate below the replacement level.

As a result, the researchers expect the number of people on the planet to peak at 9.7 billion around 2064, before falling down to 8.8 billion by the end of the century.

The number of over 80-year-olds will soar from 141 million in 2017 to 866 million in 2100.

It is a very big deal. It will become necessary to reorganise societies, say researchers.

Why are women having fewer and fewer children?

In many ways, falling fertility rates are a success story. Education, work, as well as greater access to contraception, is leading to women choosing to have fewer children.

Women, who have long propped up the global economy by undertaking unpaid work raising children, are withdrawing their free labour. With no one else willing to do that unpaid work, the result is population decline with a series of cascading economic consequences.

One such consequence is migration. We will go from the period where it’s a choice to open borders, or not, to frank competition for migrants, as there won’t be enough, say experts.

An exception to global poverty decline is Sub-Saharan Africa. Nigeria, for example, will become the world’s second biggest country, with a population of 791 million by 2100.

The distribution of working-age populations will be crucial to whether humanity prospers or withers.

Related stories

7 benefits of data visualization storytelling

Recent inflation won’t drive up interest rates. The reason is “demographic stagnation”

House prices surge as demand for offices and gyms FALL OFF A CLIFF

About the author

My name is Andy Pemberton. I am an expert in data visualization. I guide global clients such as Lombard Odier, the European Commission and Cisco on the best way to use data visualization and then produce it for them: reports, infographics and motion graphics. If you need your data visualized contact me at andy@furthr.co.uk or call 07963 020 103

Posted in: Uncategorized | Leave a Comment