The government’s Covid-19 testing programme tests only those who have Covid-19 symptoms. That’s inverted survivor bias

I woke up this Saturday morning feeling unwell.

I had headache, nausea and felt fatigued. Was this the onset of Covid-19? I live in a household with three others and am also a care giver to my 86 year old mum whom I had to take to hospital at the end of the week. Not just for my sake, I needed to know whether I might have Covid-19 or not.

I called the NHS’s testing hotline and a nice lady explained that I could not have the test unless I was displaying one or more of three symptoms: a temperature, persistent cough and a loss of sense of smell. I had none of these. I could not have a test.

Otherwize, she said, too many people would be trying to get a test.

But wait, said I. Logically if I did have one or more of those symptoms, I would have Covid-19 and would not in fact need a test. The diagnosis would be self -vident, and I could immediately self isolate for ten days without bothering the NHS at all.

The problem for me – and everyone else – was I did not know whether I had it or not. (I still don’t). So I could go around spreading the disease unknowingly or I could take time off work to self-isolate unnecessarily. The great difficulty with Covid-19 as everyone knows is that carriers can be asymptomatic. (There is currently a 28 day waiting list for a test at Boots Pharmacy while Lloyds Pharmacy home testing kits take over a week to turnaround. By the time you get a result, it’s likely you have either recovered or spread it to everyone you know.)

It strikes me the government’s testing strategy is an inverted kind of survivor bias.

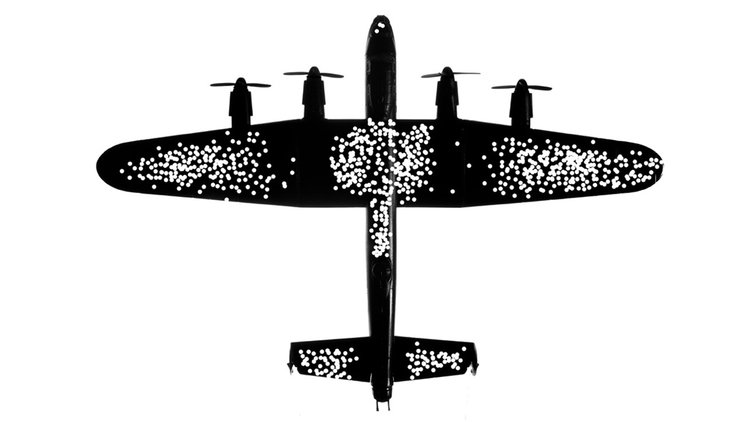

During World War II researchers at the Center for Naval Analysis faced a problem. Bombers were getting shot down over Germany. After each mission the bullet holes and damage to each bomber was reviewed and recorded. The researchers were looking for vulnerabilities The data began to show a clear pattern. Most damage was to the wings and body of the plane.

The solution to their problem seemed to be clear. Increase the armour on the plane’s wings and body.

The analysis is wrong

But there was a problem. The analysis was completely wrong.

Before the planes were modified, a Hungarian-Jewish statistician named Abraham Wald reviewed the data.

Wald’s review pointed out a critical flaw in the analysis. The researchers had only looked at bombers who’d returned to base.

Missing from the data? Every plane that had been shot down.

But the research wasn’t a wasted effort. These surviving bombers rarely had damage in the cockpit, engine, and parts of the tail. This wasn’t because of superior protection to those areas. In fact, these were the most vulnerable areas on the entire plane.

The researchers’ bullet hole data had created a map of the exact places that the bomber could be shot and still survive.

With the new analysis in hand, crews reinforced the bombers’ cockpit, engines, and tail armour. The result was fewer fatalities and greater success of bombing missions

Eight hundred people tested for every new case

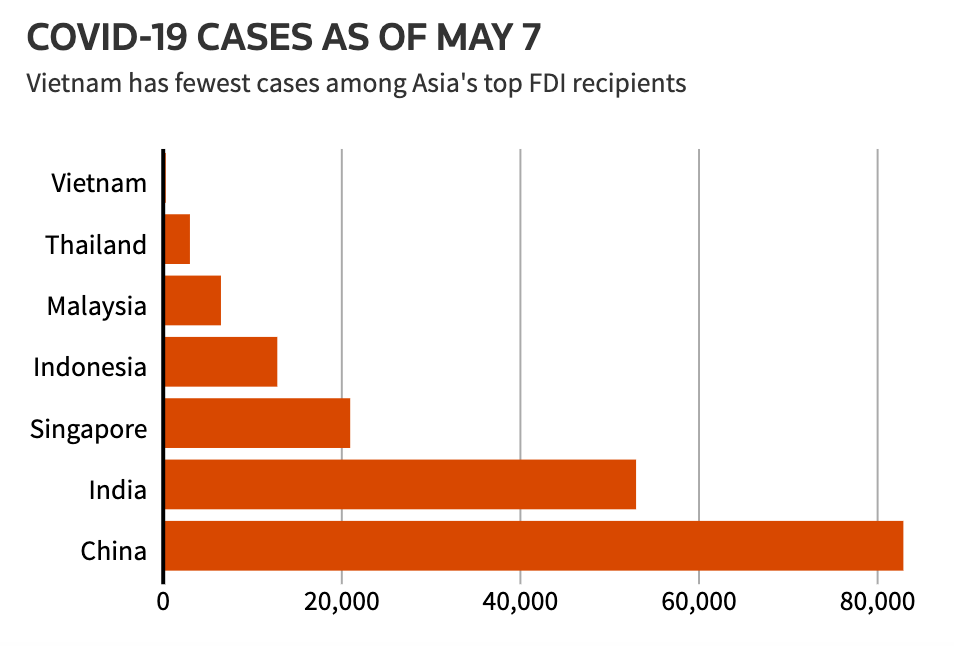

Vietnam’s strategy takes a leaf from Wald’s book. With a playbook developed to fight SARS 17 years ago, Vietnam was early to restrict travel, put large amounts of people in quarantine and tested a massive amount of suspected cases for every new patient.

So far Vietnam has tested nearly 800 people for each new confirmed case, the highest ratio in the world according to Reuters data. Vietnam’s infection rates have remained low.

Of course, this scale of testing is easier said than done and the government has promised to ramp up testing. But a strategy of testing those with confirmed symptoms seems to miss the point of testing at all.

Posted in: Infographic of the day