EVERYONE knows super-managers are not worth superstar salaries

“It’s so much harder to become a top footballer than it is to become a CEO,’’ a rather senior executive at a British public company said to me once. “That’s why they should get paid more.” This was some years before executive pay became a huge issue, and so he might not say the same today. Nevertheless, his point was intriguing, writes Furthr’s James Lumley.

His reasoning was simple: across Britain, right now, millions of boys are dreaming about playing football professionally. They are playing football at school, going to lessons at the weekend, and attending coaching camps during the holidays. Football-mad fathers are encouraging them, and fans of the sport give their time freely to encourage young players. As a result, football teams have a huge talent pool to choose from. Latent talent is shaken out. Every top player will have outperformed thousands upon thousands of other boys between the time they first kicked a ball in the yard and the day they won their first international cap. One might not necessarily like or respect every player as an individual, but it is raw talent that got them their position.

Few ten-year-old boys dream of becoming accountants. Fewer still have a childhood wish to lead a FTSE100 company. By the time a future CEO is at university, he (as it usually is a he) will probably be pretty sure he wants a career in business, and will be surrounded by quite a few equally driven, competent people who have the same goal. But when he finally takes the mantle, the numbers mean that he will have thrust aside fewer competitors to reach his position than the footballer. This, of course, doesn’t mean that he isn’t the right man for the job, but it does mean that many people who could do the job just as well, if not better, aren’t competing for the role as they are pursuing successful careers in the armed forces, teaching, politics, journalism, landscape gardening or, for that matter, any of the other jobs that little boys who don’t grow up to become footballers end up doing.

This brings me to a brilliant article in today’s FT by Simon Kuper, who has co-authored a book called Soccernomics with an economics professor at the University of Michigan called Stefan Szymanski. Writing about the sacking of David Moyes, who was canned yesterday ten months into a six-year contract, Kuper cites Szymanski’s research which demonstrates that the key determinate of a football club’s league position is its wage bill. Szymanski has looked at data from British and Italian teams over a period of ten years and has calculated that the total amount the each team’s players are paid correlates to that team’s league position by 90%. In short: if you can buy the best players, you will win the most games. Only 10% of managers (Alex Ferguson clearly being one, David Moyes another while at Everton) can raise a team higher than its ranking by total wages.

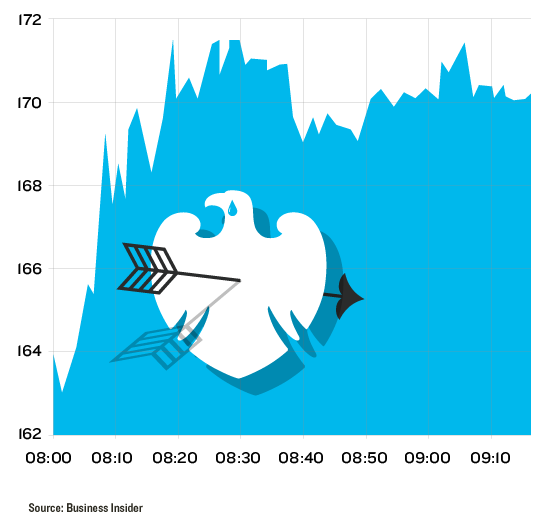

This is a statistic that probably won’t be borne in mind at Barclay’s AGM on Thursday. Shareholders are expected to voice their irritation at the bank’s decision to raise bonuses in the face of a drop in pre-tax profits. Where does the football analogy fit here? Is Barclays right to increase bonuses because, like a football team, if they pay more the bank will perform better?

If the senior executive I mentioned at the start of this article is to be believed, then the answer is a resounding no.

If, as he theorised, it is much easier to become a CEO than a top footballer, it must be statistically much much easier to become a banker on a million pound bonus. Bankers don’t regularly have their successes and failures broadcast to a huge international audience on live TV. That must mean that quite a large proportion of people on huge bonuses won’t be supremely talented individuals that the bank can’t do without, but will instead be pretty regular guys who found themselves in the right place at the right time. Do they make a real difference? Rewarding talent is all very well, as long as you really are rewarding talent, and not just throwing shareholders’ money at a problem.

The City is often portrayed as a Darwinian, dog-eat dog world where only the fittest survive.

It is interesting, then, that the average FTSE100 CEO holds his job for almost five years. As Kuper points out in his article, on average football managers hold their jobs for 497 days. That’s barely enough time to get awarded an LTIP….

Posted in: Opinion